|

Depending on the season, ESPN rotates between football, baseball,

basketball and hockey on its online scoreboard, headlines and articles.

Track and Field coverage is uncommon to rare. A brief segment every

four years after the Men’s 100 meter final in the Olympics captures the

essence of a sport which has gone the way of boxing. It wasn’t always

this way. In fact, 12 of the 100 athletes in Sportscentury (an ESPN-led

initiative to rank the top 100 athletes of the 20th century) were

incredible track and field stars. Maybe it was the lucrative development

of the “sports industry,” or the growing popularity of “team sports”

that led to track and field’s rapid descent. Probably it was a

combination of these things and additional obvious track and field

skills used modernly within TEAM sports. Whatever it was, the story that

we’re about to tell is one of the most underreported, and perhaps the

most remarkable athletic performances that the world has ever witnessed.

Wilt Chamberlain’s 100 point effort in 1962, Don Larson’s 1957 perfect

game in the World Series and even Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing

Norgay’s 20th Century ascent of Everest are relatively diminutive

compared to Jesse Owens’s feat in Ann Arbor, Michigan on May 25, 1935.

The last of ten children, James Cleveland Owens was born on September

12, 1913, in Oakville, Alabama. A host of crises—financial (his father

was a struggling sharecropper); societal (the infamous Jim Crows laws

were at their height); and medical (Jesse’s mother excised a growth

under his chest because they couldn’t afford a doctor)—forced the family

to Cleveland, Ohio. Cleveland is where Jesse would eventually meet his

first coach, Charles Riley. A middle school physical education teacher,

Mr. Riley first noticed Jesse Owens when he timed a 100-yard race on

East 107th Street. Jesse’s time, 11.0 seconds, already made him one of

the faster sprinters on the planet despite his age (he was 15), cheap

shoes, and street clothes. The world record at the time was 9.6 seconds,

and was run by adults wearing spikes on a groomed track in professional

competition. Owens and Riley remained inseparable from middle thru high

school and beyond.

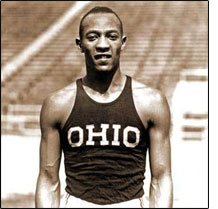

Jesse enrolled in Cleveland’s East Technical high school when he was

17. Training mostly with Riley, Owens was exposed to his first taste of

the limelight at an invitational meet in Cleveland. Several European

runners were on their way back from the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los

Angeles. Since track and field was an extremely popular sport, not

surprisingly more than 50,000 fans filled Municipal Stadium to watch a

superb track meet. The 100-yard dash was competitive and exhilarating as

Owens smashed the competition, winning in 9.6 seconds. College track

coaches from both “progressive” and “conservative” schools began to show

interest, which made for the first of many unavoidable political

debates Owens would be involved in for the rest of his career. In the

end however, Owens chose to stay close to home and attend Ohio State.

Although the university was far from being a beacon of racial progress,

the track coach was an innovator named Larry Snyder, who would

eventually accompany Owens to Berlin in 1936 where he would win four

gold medals. Snyder had made headlines for his “quirky” training

theories, which included working out to music on the phonograph. The

build up to Owens’ storied day at Ferris Field began quickly after Owens

had equaled the world record in the 100-yard dash, and subsequently

smashed the school records in the 220-yard dash and the broad jump (now

called the long jump). However, Owens was still only considered a great

college runner. His accomplishments were largely ignored because of his

race and the University of Southern California’s monopoly on collegiate

track and field—an interesting story beyond the scope of this article. Five days before the biggest meet of the season–the Big Ten

championships in his sophomore season–the “Buckeye Bullet” fell down a

flight of stairs. The injury left him with wrenching pain in his lower

back. In fact, it was said that he had to have his teammate help him put

on his uniform because Owens was unable to lift his arms over his head.

Plausibly thinking that the injury could be aggravated, Snyder had made

up his mind to pull Owens out of the meet. However, Owens made a deal

with Snyder to allow him a trial run (the 100-yard dash) to determine

his actual condition post injury. At 3:15 that afternoon, Owens

approached the starting line. As usual, everybody beat him off the mark.

Owens was known for having a below average start, but typically he

would explode like a panther after 30 yards and crush the competition.

And so the slow start was again repeated that day. Jesse was in a zone,

and the three track official timers clocked him at 9.3, 9.3, and 9.4

seconds. However, as the strict rules of the Big Ten stipulated, the

slowest time would be the official time. This stinginess probably cost

Owens the world record (he tied it instead). That was the least of

Jesse’s worries, as the broad jump was only 15 minutes away. Owens

needed to mentally and physically prepare for the ensuing event

immediately.

At 3:35 PM Owens started running towards the broad

jump takeoff board, and sprang into track and field immortality. In a

famous story, Michigan State’s athletic director claimed that Owens

jumped over his head by about a foot, and a famous photograph seems to

support his testimony. The official distance was twenty-six feet, eight

and one-quarter inches—a world record by more than half a foot. Since

the Greek Olympics over 2000 years ago, the broad jump record had moved

scarcely more than 24 inches. This was, indeed, nothing short of

amazing.

Again with little time to spare, Owens was unable to jump again

(athletes are given 3 jumps). Instead, he was due to run the 220-yard

dash. The world record was 20.6 and shared by two people. At 3:45, just

10 minutes after his record-setting broad jump, Owens ran the 220 yard

sprint in 20.3—shattering another world record. In the recorded modern

era, no one had ever set two world records on the same day (and tied a

third). Once again, Owens was due for his fourth and final event of the

day, the 220-yard hurdles. This was by far Owens’ least favorite event.

The awkward timing of the jumps while maintaining correct form was

usually an annoyance for him personally. However, at 4 p.m. Owens got

into his starting position and launched again—his fourth event in 45

minutes. Easily winning the race, Owens had broken yet another world

record by four-tenths of a second, finishing in 22.6 seconds.

Technically, Owens also set two other world records since his times in

the 220-yard dash and the 220-yard hurdles were recognized as world

records. Given that the metric record distance in these two races was

four feet shorter than the imperial distance, he also broke the world

record for both the 200-meter dash and the 200-meter hurdles. The broad

jump record set that day would stand for 25 years. Recapping, Owens had

broken five world records and tied another in 45 minutes—all with a sore

back.

As a student-athlete in the millennial generation, Owens’

record setting 45 minutes is both inspiring and refreshing. Today’s top

sports stories alternate among the removal of Joe Paterno’s statue, the

New Orleans Saints bounty program and an NFL player being arrested for

assault with a deadly weapon. This is a considerable contrast and

reflects the different sports media culture of today’s social media and

reporting world. While I understand the supposed newsworthiness of these

negative stories with the 24/7 sports media and the advertising dollars

they attract, this focus on athletes’ salaries, steroid use and crimes

of the few are overwhelming and misrepresentative. Learning about Owens’

45 minutes leads me to consider what I can achieve in 45 minutes.

Perhaps I’ll do a strenuous workout where I push my mind and body just a

little harder, ignoring the perceived pain. I’ll be inspired to work an

extra problem set for class in the wee hours of the morning. Whatever

it may be, I’ll try and do it with the same determination Owens showed

during that amazing world record setting day. In my heart and mind I

know what Jesse Owens has accomplished can be similarly achieved by

virtually everyone. That is, I believe in the true value of sports which

proves that our human limits are not static, but rather dynamic.

All biographical, athletic and scholastic information can be found in Jeremy Schaap’s book, Triumph.

References

Schaap, Jeremy. Triumph. New York: First Mariner, 2008

Photos courtesy of the Ohio State University Library Archives

|